Since its inception, the Western Growers Center for Innovation & Technology has been a credible incubator for ideas in the agtech space with the goal of bringing news from forward-thinking entrepreneurs to WG members. On the food safety front, WGCIT seeks to be more strategic and intentional around the needs of Western Growers members.

“The idea is to identify companies that are useful to our members and invite them to develop products that focus on improving the food safety tool kit,” said WGCIT Executive Director Dennis Donohue.

Donohue said those initial discussions led to a general framework of what is needed and how to prioritize those needs. What emerged from the discussions was the decision to emphasize “rapid diagnostic solutions.”

Toward this goal, WGCIT, in conjunction with the Center for Produce Safety (CPS) and the Yuma Center for Excellence in Desert Agriculture (YCEDA), launched the Food Safety Cohort in February of 2022. The cohort consists of a global group of eight innovative companies specializing in prevention technologies and rapid diagnostics that have received exclusive resources to help them launch and scale their projects.

“Rapid diagnostics that help our members get information about food safety problems sooner rather than later would be of great help,” Donohue said.

For a successful rapid diagnostic solution to be developed, he said work must be done on both the development of a test and improved sampling procedures. For the past eight months there has been a lot of discussion around the topic concerning what’s available and what needs to be developed. “Our goal is to bring tools to the market as quickly as possible,” Donohue reported. “We’ve identified the companies that fall into this sphere and now we are working with them to facilitate development. We see our role as helping to provide trials and accelerating the process where possible.”

Donohue noted that the early report card on this proactive approach to develop specific products for a specific need is good. “We’ve done a good job developing priorities and identifying companies that can make this happen. We want to acknowledge these companies and applaud their efforts. On their own dime, each of these companies has invested time and travel in the project.”

The WGCIT executive said the concept of identifying the need and proactively finding companies to work on it has proven successful. The more difficult task is getting that product to the field, but there has been progress in just the past eight months.

Currently, it takes at least 24 hours for a testing lab to deliver the results of a general pathogen test on a 375 gram sample of produce (13.2 oz.).

Javier Atencia, CEO and Founder of Pathotrak, told WG&S that his firm expects to launch a pilot project before the end of the year, which expects to deliver verified results within five to six hours. He said Pathotrak has developed the first product to deliver pathogen detection for leafy greens in this quick of a time frame and the technology has been certified by the AOAC as being equivalent to the Food and Drug Administration’s standard method.

Atencia said that any company can claim they can deliver rapid diagnostic results but unless their testing method is accredited by AOAC, no lab will use it. “We developed the technology for romaine and leafy greens, and we have now created a commercial version,” he said. “The AOAC accreditation validates our method.”

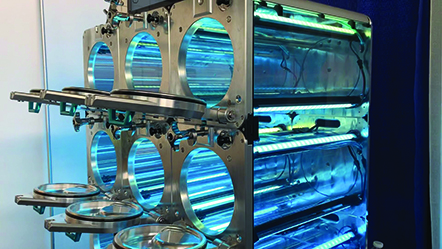

The Pathotrak method basically uses a booster to speed up the 22-hour incubation period needed to allow the bacteria in a sample to increase to detectable levels. Pathotrak’s technology can reduce that incubation period to 5.5 hours currently, and Attencia believes that over time they might be able to shorten that a bit more.

Atencia credits WGCIT and the Food Safety Cohort for moving Pathotrak into the realm of fresh produce food safety. He revealed the testing method his company is touting stems from research developed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Maryland, College Park, where he was a professor. Initially, Pathotrak was focused on developing the testing method in the meat industry. But about a year ago, Atencia talked to Donohue who encouraged him to apply to be a member of the just-forming Food Safety Cohort. “When we were accepted, we turned our attention to fresh produce,” he said.

Atencia said the connection to produce industry members has been invaluable in leading his company down this path. “I started talking to growers and discovered the big, big impact developing a rapid diagnostic test could have for the produce industry.”

Pathotrak plans to conduct the pilot project with a small select number of clients with about 10 tests a day starting later this fall. A year from now, his expectation is that the test will be available in more labs and in a greater quantity. But he cautioned that widespread use is still a couple years away. “Blue sky is 2025. By then I hope that we will have changed the food safety dynamic in produce,” he said.

Rafael Davila, who founded the startup Priority Sampling as a service company in 2016, said speeding up the diagnostic process in the lab is critical but so is speeding up the sampling process. In fact, because of the Food Safety Cohort, of which his company is a member, Priority Sampling is collaborating with Pathotrak to figure out a way to start the testing in the field even before the sample gets to the lab.

The clock, he said, starts ticking once the sample is gathered in the field. The quicker you can get the testing started, the quicker you will get the results.

Davila said when he started his company it was a “boots and bags” approach. “We would lace up the boots and walk the fields placing the samples in bags,” he said. “I would start the crews in King City and they’d move north collecting samples all day long. About 6 p.m., we would drop them off at the lab.”

That would start the 24 hour clock on testing results, meaning the results wouldn’t be available until as long as two days after the samples were collected. In the past half-dozen years, Priority Sampling has improved its process and added technology to speed up the sampling. The collection restrictions have also become more standardized, regulated and stringent.

Davila said he is working on ways to speed up the sampling and believes the effort to bring the lab to the field to start the testing almost immediately after the sample has been gathered could be a game changer. “It’s outside the box thinking, but I think it is a realistic possibility.”

When Davila started the company, he followed the KISS philosophy—Keep It Simple Stupid. Today, the company’s founder still thinks that philosophy has applicability, but he has also learned to embrace the agtech world and has come to realize that there are potential solutions to a host of issues that would not have even been considered a few years ago. “It’s the new norm and now people are accepting of ideas that four years ago they would have laughed at,” he said.

Collecting produce samples via robotic arms in the field and then simultaneously start the testing of that sample may come to fruition sooner than later. The WGCIT Food Safety Cohort has brought that far-reaching idea into the realm of possibility.