By Tim Linden

You can hardly pick up a newspaper or check out the internet without someone mentioning the Great El Niño lurking in the Pacific Ocean that will soon be peppering California with a series of strong storms.

“El Niño is on track to become one of the most powerful on record, strongly suggesting California could face heavy rainfall this winter, climate scientists say,” was the first sentence of a story in the Los Angeles Times in early September.

“Coming to the West Coast Soon! A Mega El Niño!” screamed a headline for the September 11 edition of Newsweek, which is now an online publication.

These stories all talk about the current temperature and atmospheric conditions in the Pacific Ocean, noting that the pattern is there for a large El Niño event, which historically has meant well above-average rainfall in California…particularly Southern California. In early September, the latest government El Niño forecast, issued by the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center, said that computer models unanimously favor a strong El Niño. Furthermore, the agency observed there is a 95 percent chance that El Niño will continue through the winter, which is when California would typically see its share of the rainfall caused by this environmental condition.

While the computer model generating the 95 percent probability is no doubt based on sound mathematical science, it is a bit misleading because the sample size is so small. There have not been thousands or hundreds or even tens of similar conditions to draw upon.

Mike Anderson, the official climatologist for the state of California, said there have been exactly six El Niño events in California since 1958, and they each have been different. Some brought above average rain to the entire state; others did not. “The sample size is small,” he told WG&S on September 11. “The one constant is that in each case, the south coastal regions did get above average rainfall.”

If he would predict anything, and he is clearly reluctant to do so, it would be that the coastal regions in Southern California will get above-average rain for water year 2016, which began on July 1, 2015 and extends until June 30, 2016.

In studying the six previous El Niño events, Anderson said they each shared warmer-than-usual Pacific Ocean temperatures, but they did not result in the same precipitation falling in the same regions. “That suggests there is more to the story than just warm ocean temperatures,” Anderson said.

He said climatologists are currently studying the atmospheric conditions that have occurred during those El Niño events to create more data points and come up with a better predictive model. In fact, Anderson said that during the second week of November, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography near San Diego is bringing together some of the best climatologists in the country to discuss this year’s El Niño and try to better estimate its eventual impact. Anderson is specifically interested in the findings of Klaus Wolter, who works for the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colo. Wolter is highly regarded and decorated for his predictive work on the El Niño conditions. Anderson noted that he is currently analyzing atmospheric conditions during those El Niño years searching for potential patterns or “signposts” that can be used to create more accurate predictive models. “It is very complex,” said Anderson, when asked why this is still a relatively new science. And he repeated that the sample size is very small.

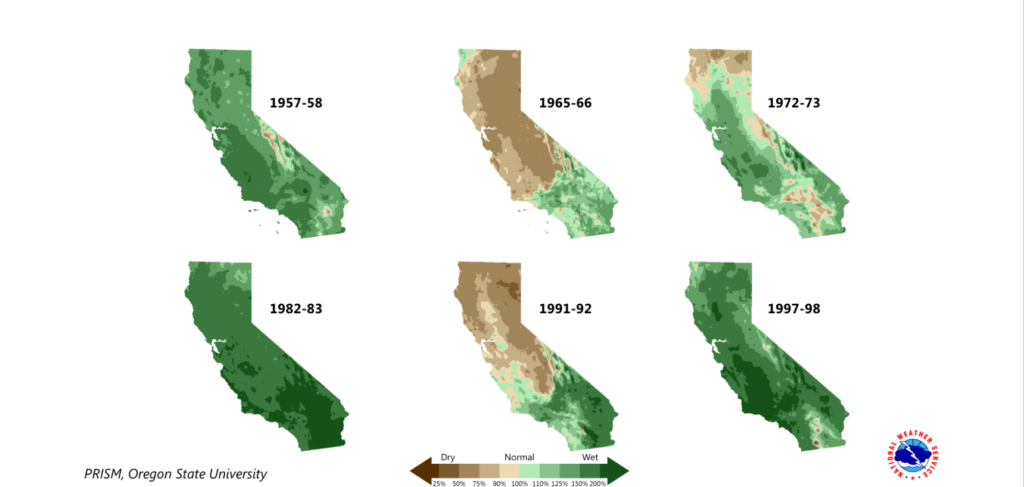

As the graphic with this story reveals, the six strong El Niños in the last 57 years occurred in Water Year 1958 (July of ’57 through June of ’58), Water Year 1966, Water Year 1973, Water Year 1983, Water Year 1992 and Water Year 1998. Water years ’58, ’83 and ’98 resulted in above-average rainfall throughout the state, with the last of those three (1998) delivering a huge amount of water. The other three produced varying amounts of rainfall throughout the state. In each instance, Sothern California was above average but parts or all of Northern California remained dry. In fact, in both Water Year ’66 and Water Year ’92, the state as a whole received less than normal precipitation, despite being in El Niño conditions. That means two of the six El Niño’s in the last 60 years did not deliver rivers of rain.

Many scientists are noting that this year’s El Niño looks more like the strong one in Water Year ’98 that any other. But there is still work to be done if it is to mirror that year.

In the Los Angeles Times article mentioned above, Stanford University Climate Scientist Daniel Swain said: “The present El Niño is already one of the strongest on record and is expected to strengthen further through the late fall or early winter months. At this juncture, the likeliest outcome for California is a wetter-than-average winter.”

Some of the effects of the El Niño have already been felt as Southern California has experienced several strong storms this summer, which is very rare. But for this El Niño to reach the precipitation levels reached during Water Year ’98, some experts say the east-to-west trade winds of the Pacific Ocean along the equator need to collapse, which would allow the sea near Peru to warm up even further.

California’s climatologist, Anderson, said the fact is that scientists do not know exactly why one El Niño has been different than another. This year’s situation will certainly add more information that can be used down the road.

He said for California, the best situation is an El Niño that gives steady rain over the length of the season to maximize precipitation and storage capacity, and minimize flooding. However, he said above-average rainfall in any area will be beneficial. While the state as a whole could use lots of rain in Northern California to fill Oro and Shasta and our larger northern reservoirs, there are lots of smaller coastal reservoirs up and down the state that will greatly benefit from any rain that’s above average. And in many instances, Anderson said the watershed can go a long way to filling a small reservoir even if El Niño delivers a series of a short-lived intense storms. He added that if atmospheric conditions do let the entire state benefit from this phenomenon—as it has done three of the six most recent El Niños—there can be quite bit of recovery, even in just one year.

Again, he said it is a complex situation that needs to factor in the location of each reservoir and its water rights situation to determine its ability to fill itself. He said some reservoirs must pass the inflow from creeks and rivers to below-dam users, and can’t just use that water to fill up a low reservoir.

In summing up just how this year’s El Niño will impact California’s four-year route, Anderson’s first comment when contacted was probably the most telling: “It depends!”

It depends on how strong the El Niño remains, where the water falls, when it falls, if it brings snow and the water rights of each reservoir. But he still allowed that, at the current time, the signs are very good.